Kangaton, Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region, Ethiopia:

A

short stroll away from the bloated Omo River in Ethiopia's far south, a

new type of settlement is forming on the outskirts of Kangaton, a

frontier town occupied by Nyangatom people and highland migrants.

The

empty domes are traditionally built: bent sticks lashed together with

strips of bark and insulated with straw. But instead of the typical

handful of huts ringed by protective thorn bushes, hundreds of new homes

are clustered on the desolate plain.

This is a site in the

Ethiopian government's villagisation programme, part of an attempt to

effect radical economic and social change in the Lower Omo Valley, an

isolated swathe of spectacular ethnic diversity.

Agro-pastoralists

such as the Nyangatom, Mursi and Hamer are being encouraged to abandon

their wandering, keep smaller and more productive herds of animals, and

grow sorghum and maize on irrigated plots with which officials promise

to provide them on the banks of the Omo.

The grass is greener

The

government, now rapidly expanding its reach into territory only

incorporated into the state a little over a century ago, says it will

provide the services increasingly available to millions of other

Ethiopians: roads, schools, health posts, courts and police stations.

But critics, such as academic

David Turton,

argue that this state-building is more akin to colonial exploitation

than an enlightened approach to the development of marginalised people.

Longoko

Loktoy, a member of the Nyangatom people, says all he knows is herding,

as he carves a twig to clean his teeth, occasionally glancing behind to

check the movements of his sheep and goats. But, he adds, "our educated

boys under the government structure" have told him life in the

resettlement site will be better.

Longoko says his family

straddles two worlds, with some of the children from his two wives

receiving education in regional cities and others raising animals in the

Omo. In line with his "educated boys", he says security and services

will improve in the commune, but wants to retain the option to move to

high land or to the Kibish River when the Omo runs low.

"I don't

think the government will tell us not to move", he says, a Kalashnikov

slung over his shoulder. Nearby, boys hunt doves by firing metal-tipped

arrows from wooden bows, while women, their necks swaddled in a broad

rainbow of beads, begin a long trudge back from the Omo with jerry-cans

perched on their heads.

Longoko is unaware of plans for the under-construction upstream

Gibe III hydropower dam

to control the flow of the Omo River, ending the annual flood that

leaves behind fertile soil for locals to cultivate on when waters

recede. The regulated flow will be used for the country's largest

irrigation project:

175,000 hectares of government sugar plantations, some of which will occupy Nyangatom territory.

"Even

though this area is known as backwards in terms of civilisation, it

will become an example of rapid development", was how former Prime

Minister Meles Zenawi

announced the scheme in 2011, heralding the final integration of the people of the Lower Omo into the Ethiopian state.

“We are from the sovereign”

In 1896, Emperor Menelik II led Ethiopian fighters to a famous victory over invading imperial Italian forces at the

Battle of Adwa

– the key moment in the ancient kingdom's successful resistance to

European colonialism. A year later, it was Menelik's turn to

expand

further, as he sent his generals out to conquer more of the lowlands to

the east, west and south. An account of the subjugation of the Lower

Omo area was provided by Russian cavalryman Alexander Bulatovich, who

Menelik, an Orthodox Christian like many Ethiopian rulers, invited to

accompany his general, Ras Wolda Giorgis, on the offensive.

The

invading highlanders faced little resistance as they marched from the

recently-conquered Oromo kingdom of Kaffa, a place Ethiopians claim to

be the birth of coffee, according to an account of the trip translated

by Richard Seltzer in

Ethiopia Through Russian Eyes by Alexander Bulatovich.

“If

you don’t surrender voluntarily, we will shoot at you with the fire of

our guns, we will take your livestock, your women and children. We are

not Guchumba (vagrants). We are from the sovereign of the Amhara

(Abyssinians) Menelik”, the Ras told local chieftains when he arrived in

an area slightly to the south of Nyangatom territory where the Omo

flows into its final destination, Lake Turkana, which mostly lies in

Kenya.

“A civilising mission”

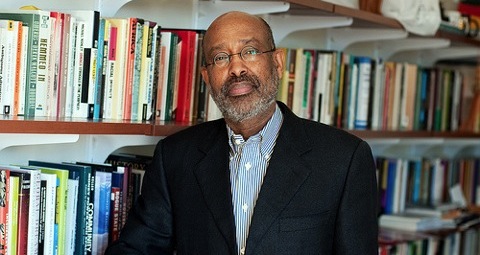

Anthropologist David Turton

from the African Studies Centre at Oxford University has been visiting

the Omo valley and particularly the Mursi people since the 1960s. He

sees the current approach of the ruling party to development and

state-building in the south, with its "civilising mission" and "racist

overtones", as similar to that of previous regimes, going back to

Menelik.

Schemes imposed from the centre that force people off

their land are bound to create resistance, he believes, although direct,

violent forms of protest are inconceivable given the overwhelming power

of the state. In the past, there was space for people like the Mursi to

move out of the way of the state. Today, he says, they know this is

impossible.

“They know that they are practically finished”, he

explains. “Their way of life, their livelihood, their culture, their

identity, their values, their religious beliefs – all this is being

rubbished by a government which sees them as ‘backwards’ and

uncivilised. No human being could fail to feel threatened by this,

physically and morally.”

At the core of Turton's dismay are the

accumulated findings of research on ‘development-forced displacement’.

This shows, he says, that people who are forced to move to make way for

large-scale development projects always end up worse off than they were

before, unless concerted efforts are made to prevent this.

"Ideally

the government would have taken them into its confidence from the

start, given them full information well in advance, fully consulted them

about its plans, included them in the decision-making, and provided

proper compensation for the loss of their land and livelihoods" he says.

But

instead, Turton claims, none of this has happened, and the result will

be increased poverty among the many ethnicities that populate the Omo

valley. That was the fate of Oromo and Afar pastoralists when Emperor

Haile Selassie applied a similar top-down method to Ethiopia's first

major river basin development on the Awash River in the 1960s, he

explains.

For the greater good?

Marking a departure from

the past, the ruling Ethiopian Peoples' Revolutionary Democratic Front

(EPRDF) argues that since it seized power in

1991,

it has empowered rather than oppressed the over 80 ethnic groups that

live in the Horn of Africa nation. This is done through an innovative

system of ethnic-based federalism that enshrines the right of each group

to govern itself and protect its language and culture. Critics,

however, counter that centralised policymaking and the de facto

one-party system that maintains political control denies autonomy for

regional actors. This tension can be seen in attitudes to nomadic

people: while Ethiopia's 1994

constitution

guarantees pastoralists the right to grazing land and not to be

displaced, previously in 1991, the EPRDF adopted a policy "to settle

nomads in settled agriculture", according to a Human Rights Watch

report from that year.

In

the official narrative, sugar plantations and the new communes in the

Omo are consistent with ethnic federalism, as they will reduce poverty

and bring some trappings of modernity to minority groups.

"In the

previous backwards and biased government policy, there wasn’t a

systematic plan and no meaningful work was done for the pastoralist

areas”, Meles said in his

2011 speech. “Now we have started working on big infrastructural development."

This stance is reinforced by pro-government media such as the

Walta Information Center, which, in a

recent article,

presented the projects as unanimously welcomed by local people. “We had

no strength when we have been living scattered. Now we have got more

power. We are learning. We are drinking clean water”, Walta quotes Duge

Tati, a local in Village One, as saying. Another villager was said to

aspire to own a car.

However, reports from advocacy groups such as

Human Rights Watch and

Survival International

present a starkly opposing view on recent development in Omo. They

contain countless accounts from locals detailing how they've been

coerced and beaten into accepting policies that steal their land and

ruin their livelihoods.

They are a-changing

The Nyangatom

have historically been so peripheral to Ethiopia's highland heart that

in 1987 the Kenyan government bombed them with helicopter gunships in

the Kibish area after a particularly murderous bout of ethnic clashes.

Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam, Ethiopia’s nationalist military dictator at the time, allegedly assented to the operation.

Today,

officials from Kangaton, the administrative capital, have to take a

boat across the Omo to attend meetings with regional bosses. Despite

this isolation, the impact of missionaries, traders and government is

displayed in aspirations for services and technology, and the adoption

of non-traditional dress and cuisine – at least among some people living

in or near Kangaton.

Lore Kakuta is a Nyangatom who became a

Christian after attending school run by missionaries. He is also the

security and administration chief for the Nyangatom-area government.

Wearing a replica Ethiopian national football team shirt and a head

torch bought in Dubai, he sketches out the plans for irrigated

agriculture and a shift to cows that produce more milk.

Lore is

uncertain about how much Nyangatom land will be lost to sugar

plantations. And he is clueless about the hundreds of thousands of

migrant workers that it is said will soon be attracted to the area, and

the impact they could have on his people's welfare and their

constitutionally-guaranteed rights. Nyangatom culture is strong enough

to withstand any influx, he says, weakly.

As a meal of goat stew

mopped up with flat bread from the Tigrayan highlands is served, he

explains how the traditional culture has changed already, mainly due to

the influence of missionaries. So for Lore, the imminent transformation

is nothing to worry about.

"There is not anything that is going to

have a negative effect", he says, now garbed in a billowing traditional

robe after dusk inside his compound. "We are teaching people to

modernise."

------

Think

Africa Press welcomes inquiries regarding the republication of its

articles. If you would like to republish this or any other article for

re-print, syndication or educational purposes, please contact: editor@thinkafricapress.com

,+General+Julius+Karangi.jpg)